- Home

- David Epperson

The Third Day Page 3

The Third Day Read online

Page 3

“Henry remembered that his father had a savings account that he left untouched for years, so we sort of borrowed it for a while. We had a lawyer draw up all the documents; then we printed them on a font commonly used in the 1970s and sent them to the bank’s trust department. The documents contained specific instructions for the disposition of our account, as well as the return of his money, with interest and a substantial return for his trouble.”

“When did you know it worked?”

“Last fall, Henry sent the papers while I logged in to our account. A few seconds later, our bank’s web site showed the totals change. It was quite thrilling.”

Incredible.

“So you finished the rest of the project with your own money?” Markowitz asked.

“We didn’t feel like we could go back to your father for more funds without disclosing what we had achieved. Once we confirmed our initial hypothesis, it was merely a matter of expanding on our previous work.”

I laughed. “Merely?”

She smiled. “It may have been a bit more complicated than that. After a few more months of work, we eventually succeeded in transporting a three dimensional object, using the mechanism you saw below.”

“Nothing living could survive that level of cold,” said Markowitz.

“No. The transport facility is immediately above the quantum processor. I’ll show it to you later, when everyone has gone home. Only one other member of our staff knows that it exists.”

Markowitz closed his eyes as he stretched his hands over his head; then he turned to me. “I’m still not sure I believe this.”

I wasn’t sure what to believe, either. All I could muster in reply was that her explanation seemed to square with the facts as we knew them.

I did have a question, though. “You keep using the word ‘we.’ Can you tell us where your other half is now?”

Juliet didn’t answer. Instead, she flipped open her phone and tapped a quick text message before turning to a side door that I had not noticed earlier.

“Excuse me, gentlemen. I need to check on something in the lab. I’ll be right back.

Chapter 5

Juliet returned a few minutes later and beckoned us to follow her into the facility’s conference room. She had furnished it, like her office, with good quality second hand stuff, but that wasn’t what drew my attention.

I had thought the lab kept itself out of the public eye, but seated at one end of the long table were two other visitors. The man was dressed in jeans, old boots and a work shirt that would have fit in on any of the city’s burgeoning construction sites. Though not rugged, he clearly spent a fair amount of time outside.

I pegged his companion to be in her late 30s; a natural blonde who, a decade earlier, probably caused traffic accidents. Her face still retained its youthful luster, and from her fit, toned arms, I surmised that she didn’t sit on the couch all day gorging on potato chips and watching talk shows.

Juliet introduced the four of us. Our new acquaintances were Sharon Bergfeld and Dr. Robert Lavon – what type of doctor, she didn’t say.

Markowitz hadn’t expected company, either. Though polite, he was clearly unhappy.

“Dr. Bryson, I’ve always assumed that the work of this facility would remain confidential. Our contract specifies – ”

“I’m aware of the contract, Ray, but I also understood that you were interested in the whereabouts of my husband.”

“We are,” he replied.

“My guests found him. They arrived a couple of days ago. Since I knew you were coming, I asked them to stay.”

This was a surprising turn of events.

“OK,” I said. “Where is he?”

“Israel,” said Lavon. “I’m afraid Dr. Bryson is dead.”

I glanced over to Juliet, but I couldn’t think of anything to say except that I was very sorry. I found the news so unexpected that I failed to notice that her demeanor didn’t exactly match that of a woman suddenly bereaved.

Lavon unfolded a map of Israel and turned it so that Markowitz and I could read it easily. He had drawn an X where they had located the body – just off the freeway bisecting Jerusalem’s outer western suburbs.

“We found him at this site, about three weeks ago,” he said.

“What on earth was he doing there?” asked Markowitz.

I could think of a number of reasons. Veterans of the Israeli army had turned the country into one of the world’s burgeoning tech centers. Perhaps someone had offered him a better deal.

I glanced again toward Juliet, but she didn’t volunteer an answer.

“Have the police released their initial report?” I asked. “If not, one of their investigators owes me a favor. I’d be happy to make a few calls to speed things along.”

“Thank you,” she replied, “but I doubt that would help.”

“Why not?” I asked.

In my dealings with them, the Israeli police had exhibited the highest levels of competence and professionalism.

“Because, um.”

She gave Lavon a fleeting look. Go ahead.

“The police wouldn’t be interested because the tests we ran on his skeleton indicated that Dr. Bryson died approximately two thousand years ago,” he said.

Markowitz nodded, just as he had when Juliet explained the source of their great wealth. A few seconds later, though, Lavon’s words registered.

“Two thousand what?” he blurted. “Did you say two thousand years?”

Lavon handed him a computer printout. The younger man quickly scanned it before tossing it back.

“Radiometric Labs, Tel Aviv. What are you people trying to pull? What kind of doctor are you, anyway?”

“My Ph.D is in archaeology – University of Michigan, with honors. Go check if you’d like.”

I made a note to do that, but he didn’t seem like the type of person who would lie about something so easily verified.

He held up another printout.

“We found the initial results to be as incongruous as you do now, so we headed back home to retest our findings with two independent labs here in the States. None of the three facilities had access to the work of the others.”

“I assume they reached the same conclusion?” I asked.

“They did,” said the woman. “We also found some fragments of cloth near the bones. These dated to the same period as the skeleton.”

She spoke with that soft Texas twang that drove my Army buddies crazy.

Markowitz paid no attention to that. He stared at them, making no effort to conceal his skepticism.

“That would be expected, wouldn’t it?”

“Yes,” she replied, “except the fabric was sewn by a machine, the thread had a polyester core, and fiber analysis revealed that the cotton surrounding the core – fiber dating to the first century – was itself spun from a genetically modified strain, originally native to the Americas.”

They passed the reports to me – all on official looking letterhead that either could be authentic or the creation of a halfway decent graphic designer with a laser printer. It was so hard to tell these days.

“Tell me, Doctor,” I said, “how did you determine that the bones belonged to Henry Bryson? I don’t think they wore dog tags or carried driver’s licenses two thousand years ago.”

Lavon reached into a gym bag and pulled out a clear plastic cylinder, resembling the ones used by banks at their drive-in windows. He tossed it over to me. Inside, fixed in place with bubble wrap, were the distinct bones of a human finger, held together by a metal pin.

“We traced the serial number on the pin to the hospital, which connected us to a surgeon’s office, which ultimately linked us with Juliet here.”

“He enjoyed woodworking and accidentally sliced his finger off with a band saw several years before you first met him,” she said. “Some fine surgeons over at Mass General sewed it back on and eventually he made a full recovery. He didn’t even notice it after a while. It was almost as if

the accident never happened.”

I reached into my jacket pocket and took out my reading glasses, better to focus on the pin. As a veteran of the Army special forces, I was all too familiar with bone fractures and this particular medical technology.

“You dated the specific bone, around the pin?”

“You have the printouts right there,” said Lavon. “We’ll make a copy for you, if you wish, for later study. Take all the time you need.”

“DNA?”

“None recoverable from this specimen.”

I rolled it around a couple of times. “This pin wasn’t simply drilled in later?”

“That was our first thought, too,” he replied: “somebody was playing a trick on us. It happens all the time in our line of work. That’s why we confirmed the results with completely independent labs. I hand carried each of the specimens as well, to ensure the integrity of the chain of custody.”

I glanced back down at the cylinder.

Now I’ve heard some whoppers in my day, and in my business, I had to deal all too often with people who were, as Twain famously put it, “economical with the truth.”

On the other hand, Juliet Bryson had not tossed them out straightaway, which is what I would have done to anyone spinning such a tale, unless …

“Dr. Lavon, you mentioned bones, plural. I presume you recovered the rest of the skeleton.”

He nodded. “This fragment and our small test samples were the only portions the Israeli authorities would allow us to take out of the country.”

“Where are the other bones now?”

“At the lab, in Tel Aviv. I can show you, if you’d like to see them.”

***

I assessed both visitors closely once more. Truly pathological liars often have the innate ability to inspire confidence, which is why certain types of investment swindles remain so consistent over time.

But if the Brysons’ work, and fortune, had in fact remained unpublicized, I couldn’t figure out what these two could have hoped to gain from their story.

“Yes,” I replied, “I would like to see the bones. Actually, I’d like to go through the entire sequence of events that led you here, starting from the very top.”

“Certainly,” he said.

I held up the tube. “I can’t exactly go back to my client and present this as definitive proof of Dr. Bryson’s whereabouts.”

Chapter 6

That was how I found myself on the next El Al flight out of New York. Markowitz couldn’t go; he had a social commitment he couldn’t avoid without the gossip columnists taking note, but he did agree to give his father only a basic outline of our findings until we had a chance to make further inquiry.

Sharon, too, chose to stay behind, for reasons she didn’t elaborate.

While we waited for our flight to board, Lavon explained that her father, a Dallas real estate developer, had provided the lion’s share of their excavation’s funding for the past several years.

He wasn’t just any developer, either. According to the Wall Street Journal, Edward Bergfeld, Jr. owned the second largest collection of Class A office buildings in the United States, and it came as no surprise to hear that he also ranked among the top contributors to conservative religious and political causes.

“Do you have a sense of Sharon’s own views?” I asked.

Lavon paused to consider the question.

“Somewhat like her father’s, from what I can tell,” he replied, “but I’ve learned not to probe. In our business, we take funding where we can find it. The old man seems satisfied with our current arrangement and I don’t want to jeopardize our work by getting into unnecessary theological disputes.”

I nodded. This made perfect sense.

“How much time has she spent at the site?” I asked.

“She visited for the first time earlier this year.”

“Does she have any archaeological training?”

“No. She just happened to be there when we uncovered the skeleton; but I’ll give credit where it’s due: She was the one who initially noticed the polyester core in the thread. The brand is called D-Core; it’s quite common today.”

Since others waiting at the departure gate could overhear our conversation, we agreed not to discuss further specifics until we reached our destination, though I couldn’t resist making a final pass through online databases before having to shut the system down for takeoff.

***

Considering that I had made my last trip to Israel in the back of a noisy, windowless C-130, I couldn’t complain too much about having to fly coach. We landed about six the next morning, cleared immigration and customs, and were comfortably ensconced in our rental car by eight, crawling slowly forward in Tel Aviv’s rush-hour traffic.

Half an hour later, we pulled into the parking lot of Radiometric Labs and greeted the friendly receptionist. She escorted us to the back, where two technicians had laid out the skeleton on a metal table in the center of the room.

“I called ahead,” said Lavon.

We introduced ourselves. Radiometric’s manager, Jonathan Dichter, had studied with Lavon at Michigan before returning to his native country.

The lab was arranged in a typical fashion. A long bench ran the entire length of one side, covered with an array of beakers and reagents, an autoclave and couple of laptop PCs – though I suppose I should qualify the term “typical.” Old movie posters of Godzilla breathing fire upon Japanese cities festooned the walls.

“Two thousand years from now, confused scientists might attribute the destruction of our present world to such a cause,” Dichter explained.

I shrugged. To each his own.

We chatted a few more minutes and then got down to business.

“When did you first realize you had a problem?” I asked.

“Let me start by explaining our normal procedures,” Dichter replied.

“When a skeleton comes in from an excavation site, we lay it out on the table and count the bones, to determine whether it is completely intact and to resolve the question of whether two or more sets of bones may have been mixed together.”

“Fair enough,” I said.

“Then we take preliminary measurements of the long bones and x-ray everything.”

“That would have picked up the pin, wouldn’t it?”

“That’s correct, if our equipment had been working. Our machine broke down a few days earlier, but the local hospital had priority access to the parts we needed. Getting it repaired took over a week.”

“That’s when you found the pin?”

“Yes, but by then that was only one of many anomalies,” said Lavon.

Dichter continued, “From the femur length, we estimated the man’s height at 185 centimeters. That’s six foot one to you Americans; tall for the era, but not Goliath.”

From my recollection of Henry Bryson, that sounded about right.

“Once we did that,” Dichter said, “we took random samples of the bones and calculated a preliminary age using a standard radiocarbon process. In this case, the results dated consistently to the first century, with a margin of error plus or minus a decade or two.”

“This all seems rather straightforward,” I said. “When did you first suspect that you were dealing with something out of the ordinary?”

Dichter reached up to grab a bright circular lamp, similar to the type found in a dentist’s office. He turned the skull toward me and focused the light.

“Let’s see if you can do any better than I did,” said Lavon. “Tell me if you notice anything unusual.”

I studied the skull for a couple of minutes, but nothing looked terribly out of place. “I can’t see anything,” I finally said.

“Count the teeth,” Lavon instructed.

I did so. “23.”

“The normal adult human has 32,” said Dichter.

“Right, but didn’t everybody lose teeth two thousand years ago?” I asked.

Dichter and his assistant both laughed

. “Robert said the exact same thing.”

I examined the skull again. The odd thing was, I saw no gaps between the teeth that remained.

“Ah,” said Dichter. “Now we’re getting somewhere.”

“That’s what we first noticed,” said Lavon. “Plus the loss of teeth is symmetrical. The bicuspids are missing, top and bottom, as are the wisdom teeth.”

“The left side of the upper jaw is missing one more,” I said.

“The second molar,” replied Dichter. “We extracted that one ourselves to run a separate test, using the Electron Spin Resonance method as opposed to radiocarbon. ESR is ideally suited to dating tooth enamel, but it requires input in powdered form.”

“We had to grind it up,” said Lavon.

“And?” I asked.

“First century, more or less. ESR is not as accurate as radiocarbon, but the tooth was definitely not modern.”

***

None of us spoke for a while as I considered this.

“Now you know what we’re up against,” Dichter finally said. “Until a few years ago, orthodontists regularly pulled teeth before installing kid’s braces, but I’ve never heard of such a thing in the ancient world.”

“I’m not sure I’d want to,” Lavon joked.

I certainly didn’t.

“Could someone have grafted the teeth in later, like, um …”

“Piltdown Man?” said Lavon.

Both archaeologists laughed. “Discovered” by an English professor in 1912 and heralded for years as the missing link between ape and human, Piltdown Man remained one of archaeology’s most well-known frauds. Later examination revealed the specimen to be an orangutan’s jaw with chimpanzee teeth, attached to a medieval skull.

“I don’t think so,” said Dichter. “This jaw showed no signs of tampering at all. Although it took scientists forty years to prove Piltdown a hoax, we’d spot the same thing in minutes today.”

“That just means the fraudsters have to be smarter,” I said.

Lavon and Dichter laughed again. “They are.”

The trade had become a never-ending game of cat-and-mouse. A renewed interest in ancient history, compounded by rising affluence across the globe, had created a growing pool of new and relatively unsophisticated buyers.

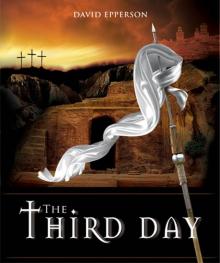

The Third Day

The Third Day